In Hume’s “Of the Standard of Taste”1, we are presented with a sometimes confusing picture of the aesthetic world. On one hand, Hume is quite explicit in saying that aesthetic properties are dependent upon beliefs of aesthetic agents; they are parasitic on sentiment. However, Hume argues that there are nevertheless clear standards of taste, which dictate the correctness of our various aesthetic judgments. Here I wish to present a loose interpretation of Hume that takes the psychological nature of aesthetic judgments seriously. Following work by Jerrold Levinson, I claim that aesthetic standards can only be understood from the perspective of prediction; we want to have an aesthetic standard of taste so that we can predict which works will bring us the most aesthetic pleasure. Furthermore, if we consider this issue from such a perspective, the more troubling issues of Hume’s view fall away.

What does a psychological model look like?

I find it uncontroversial that aesthetic properties are mind-dependent even though it may be profitable for us to talk about such properties as real in a substantial way; this makes it somewhat obvious to compare aesthetic properties to perceptual properties, which seem to have a similar ontological status. There is clearly a “standard of perception”; if two observers are looking at an object and one person says that it is red while the other declares it to be blue, there is a clear method by which we can find out who is correct. There is a consistency test that can be applied in this sort of situation because certain perceptual judgments are supposed to map onto properties of the objective world; in the above situation we could simply bring out the spectrometer and resolve the issue rather quickly. In vision there are clear standards for what a normal perception will consist of and if an actual perception deviates too greatly from this standard then something has gone wrong. Barring some sort of difference in language usage, this sort of deviation represents an error in the perceptual processes; something is wrong with the person who guessed the incorrect color. This might be due to any number of situational issues (the lighting might cause an optical illusion where the incorrect person stands) or problems with the perceptual system itself, but there is little doubt about who is seeing correctly.

One could treat aesthetic properties as they do perceptual properties; both are mind-dependent but they also have clear standards by which we can discern the correctness of judgments. The standard of taste might be far more difficult to discover than the standard of perception but this is simply because the ways aesthetic properties interact are far more complicated than perceptual properties. I want to dig a little deeper into this line of reasoning because I think it has some merit. First, it is important to understand the way our perceptual standard works. One important question is how we measure the quality of a perceptual system. There are certainly people with better and worse perceptual systems; some are unable to detect certain colors or shapes when they should be able to whereas others are able to perform these sorts of tasks with great precision. The case I want to deal with is acuity in color judgment. One common test of color blindness is the Ishihara plates method which presents a form (typically of a number) that is only visible to those with normal color discrimination. Those who are color blind will not differentiate between dots belonging to the form and others that interfere with it. So, it seems tempting to say that a good perceiver is one who is more precise and can make more differentiations. If this sort of standard holds then one can say that there is a clear objective standard of perception, namely how precise our judgments are; we can ground our normative statements (at least the direction of them) about perception in something outside of the actual norms that occur in human vision.

However, this objective standard is complicated by a case where heightened sensitivity falls too far above the norm. This is the case for tetrachromatic women who have four color cones instead of three; this causes them to make far more differentiations between wavelengths.2 One might initially think that it is ‘better’ to have this ability; however, it could cause a great deal of trouble as well because those with four cones must live in the world created by three-coned (trichromatic) people. This means that aesthetic objects that may look fine to trichromatics may be quite ugly to tetrachromatics; fields of color that appear uniform to trichromatics would instead be full of sections of clashing colors for tetrachromatics. In this case, it seems that it is worse to be able to see the world with greater precision if the world (especially the world of artifacts) itself does not give benefits for this precision.3 This points to something more complicated setting the normative nature of perceptual capabilities; good perceptual judgments are those that allow us to obtain relevant benefits. We simply cannot decide on the normative structure of perceptual judgments until we consider why we concern ourselves with those judgments in the first place.

It seems that even normative assertions for perceptual properties are somewhat complicated; however, there is also reason to believe that aesthetic properties will be even more problematic. Though perceptual and aesthetic properties don’t seem to differ in any large qualitative way, the structure of the perceptual world does differ from the aesthetic in a very important quantitative way. There is some variance in how our perceptual systems work; however, there is far more variance in our aesthetic judgments.4 The structure is certainly tighter in the perceptual case; a stimulus that has a luminance of 50 cd/m2 may sometimes be judged as indistinguishable from one that is 51 cd/m2 but this is almost never the case for something 65 cd/m2.5 Additionally, this structure can be obtained from people who have no experience with luminance discrimination experiments; the simplicity of perceptual judgment is remarkable when compared with that of aesthetic judgment. If one would try the same thing in the general public (with the same population that performed the brightness task) with two pieces of music, we would never find such clear results. We can imagine selecting two piano pieces, one by Debussy and another by Jim Brickman; the results will certainly be messy and not at all consistent with the fact that Debussy is the better composer. This sort of comparison is unfair in a certain sense because one can’t simply expose random members of the public to an amazing piece of art and expect them to recognize its brilliance. It is true that they will probably like such a piece to a certain extent, but many won’t recognize how great it is. Meaning, a comparison between a mediocre (though maybe not terrible) piece and a brilliant one will produce judgments that do not reflect that brilliance.

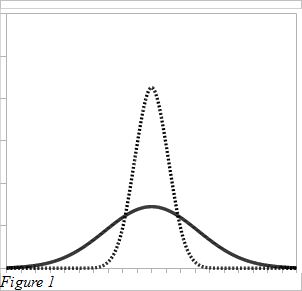

It might help to make this talk about these distributions more explicit by actually drawing them out. Figure 1 (below) shows two normal probability distributions. The x-axis for all distributions is of some continuous variable; for both perceived brightness and judged aesthetic quality values increase to the right. The y-axis represents a percentage of the total population, with the area underneath a curve always being equal to 100% because the curve spans all possibilities of the x-axis variable. The dotted line is a distribution with a relatively low variance; the curve is similar to what would be obtained when a population is asked to rate the brightness of an object.6 These sorts of processes are known as being cognitively impenetrable; this means that conscious cognitive processes can not interfere with the perceptual process.7 The impenetrability of these non-cognitive processes contributes to this low

variance. The solid line is a process with a larger variance; this might be an idealized version of a more cognitive (and therefore more complicated) process that produces a distinct standard but with a far higher variance.8 If we are able to find a distribution of aesthetic judgments it would almost certainly be of a higher variance like this because of the greater effect of individual differences.

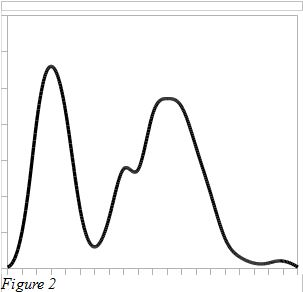

However, aesthetic judgments involve a cognitive process that is not only high in variance but also not necessarily normally distributed, at least from the initial polls of peoples’ judgments. Something like Figure 2 might result from such a poll.9 However, we can tell a story about this sort of distribution since there are clearly regularities. We can imagine that Figure 2 (below) represents the ratings people might have given someone like the singer Britney Spears in her early career; although many people found her to be quite terrible (the left peak), another large group thought she was quite good (the peak in the middle). Notice that even though we can likely explain these regularities with various causal theories (utilizing what we know about the comparative tastes of those who found her music to be either good or bad), there doesn’t seem to be any single standard that makes sense. Any standard that we come up with will require the  dismissal of the opinions of a large group of the public. Even if we think this is a good method to use, we have to recognize that the fact that we have to do this produces a large dis-analogy with the case of standards in human perception.10

dismissal of the opinions of a large group of the public. Even if we think this is a good method to use, we have to recognize that the fact that we have to do this produces a large dis-analogy with the case of standards in human perception.10

At this point it might be tempting to think that the perceptual system tracks some objective property in the world and therefore the standard we can use is not based upon the behavior of the perceptual system itself but instead the properties of that object in the world. But this would be a mis-characterization. Most scales of perceived magnitude in our perceptual system operate on a logarithmic scale; this means that as the absolute magnitude of the stimulus increases, ever larger differences between magnitudes are required for there to be a perceived difference.11 If our perception was veridical then we would expect the noticeable difference required to remain the same regardless of absolute magnitude. So, in a sense, our perception of magnitudes tends to flatten out as the absolute magnitude of the property in the world increases. However, we would still say that a person who had judgments consistent with this flattening is observing “correctly;” although that perception may not be veridical, it is still normal. If we don’t take this line and instead assert that error exists every time perception does not match objective reality, then we run into the problem of having to say that the tetrachromatic perceiver is more correct than we are. Although this could be one way to talk, it seems to throw the standard into irrelevance; we can never hope to be able to make the sort of color distinctions that the tetrachromatic is capable of making so there is no reason for us to even consider these capabilities when we seek to guide our own actions.

Relevance and Hume’s Standard of Taste

For my view of aesthetic standards, I will use the so called ‘subtext’ of Hume’s “Of the Standard of Taste”12 as a starting point. According to this subtext, Hume proposes a standard of taste that is based upon empirical facts about people’s aesthetic behaviors; he proposes that we use works of art that have been universally judged as being aesthetically excellent. These are works that, through the ease with which they have caused aesthetic pleasure in many varied observers, represent some sort of purity of aesthetic force. However, these works cannot be used directly as a standard because it seems unclear how attributes of one work can be used as principles in deciding the merits of a different work that has an entirely different dynamic. For this reason, these master works are used to select ideal critics who both judge the master works to be especially fine and who also have a deep understanding of what makes those works excellent. Hume also proposes that these critics will have five additional attributes: “Strong sense, united to delicate sentiment, improved by practice, perfected by comparison, and cleared of all prejudice…”13 So, although most of us like these master-works (such widespread appeal is a requirement to be a master-work), an individual must also have certain general aesthetic skills to ensure that they are properly engaging with the works that they will judge. Hume thinks that critics chosen in this way could, in a sense, act as an aesthetic test; their judgments about non-master works would set an aesthetic standard that informs us of their relative aesthetic quality.

It seems apparent that the sort of master works Hume posits do in fact exist; pieces like Beethoven’s 5th Symphony or Shakespeare’s Hamlet consistently cause aesthetic pleasure in people. But if we explicate this a little bit, it seems that such a procedure is not necessarily guaranteed to give us judges who are able to provide judgments about artwork that are relevant to us. This issue of relevance was initially raised by Levinson14 as a response to his concern of why we should care about the judgments of ideal critics at all. His thought was that we would only really care about the judgments of ideal critics if we thought that to do so would bring us more aesthetic pleasure. This has a great deal of prima facia plausibility in that it often seems to be the reason we listen to any sort of critic; by listening to a critic we expect to be able to make the decision of whether we should invest time in a given piece of art and are also informed of how we might enjoy a work more if we do devote some energy to its enjoyment. This is contrasted with the view proposed by Jeffrey Wieand, who claims that the standard formed by ideal critics is best used to inform us about what sort of people we are.15 Wieand has doubts that we can actually adjust our taste in any substantial way and therefore the true judges simply tell us whether we have good or bad taste based upon the extent to which we agree with them.

Levinson himself dismisses this sort of reply and I think he is right to do so, but let us dwell on it for a little longer because I think it reveals something of how we should think about aesthetic properties. What would one have to believe about aesthetic properties to be concerned with the judgments of ideal critics even if they had no hope of attaining those preferences? It would have to be the case that something normative could be automatically derived from a given standard. Remember that, even in the case with tetrachromatics, there doesn’t appear to be any urge to compare our own ability with theirs. In fact there is some sense in which tetrachromatics are worse off because of their better color discrimination, as it may leave them less satisfied with the aesthetic world around them. The only option I see open to Wieand is that truly good aesthetic experience taps into some sort of deep truth about reality and we must respect this in some way regardless of our own interests. This could be similar to the common view of IQ; even though we know that little can be done to raise our IQ score, most of us still take it seriously.16 However, this is because we typically think of IQ as extremely useful for other things that we value; those who have a higher IQ will, all other things being equal, have an easier time undertaking their life projects. So, a normative valence is attached to IQ in most people’s minds. Wieand thinks that we can attach the same sort of normative valiance to aesthetics so that no general consensus about the identity of master works is needed for us to decide who the ideal critics are; for him, the 5 attributes (that I described earlier) of ideal critics are enough to tell us who is capable of making the best possible aesthetic judgments.

Though Wieand may view aesthetic taste as almost automatically normative, this is far more difficult for the empirically minded. It seems most probable (as I discussed in the previous section) that aesthetic properties and judgments are psychological phenomena and any concern we have for them are derived from a more basic wish to experience pleasure (in the broad sense of the word). So, our concern is not so much about finding those who are experiencing the most exceptional and refined aesthetic pleasure so that we can sit back and wish we were so lucky, but instead is to find the general regularities in aesthetic pleasure that could help us to infer what aesthetic objects would bring us pleasure. This demand for relevance makes Hume’s scheme to find a standard of taste into an empirical theory about what sort of model will have the best predictive power.

Before going any further, I have to first revise the way I have been talking about aesthetic preference. Up until now, I have treated aesthetic preference as if it could simply be polled straightforwardly, as if we could take a random sample of people and ask them to compare Beethoven’s 5th Symphony and Handel’s Messiah and expect to get some sort of meaningful measure of the relative aesthetic enjoyment of the two pieces. However, most art requires at least some knowledge or skills in order for its full impact to be felt. So, it seems that what we should really be after is the sort of enjoyment that we are capable of obtaining from a given piece of art and not what we experience when we encounter it in a very superficial way. Although the capability notion seems to fit what we want to know far better, it makes our job quite a bit harder. It is not immediately clear how we can come to know our capabilities of aesthetic enjoyment with accuracy. However, I will leave this epistemic worry for later because it seems to be extremely common with psychological theories and there might be some ways we can come up with answers that are good enough to give us accurate predictions about what sort of art to pursue.

However, there is a second worry about the capability approach; it seems unclear how much one must dedicate to a work (or group of works) in order to still be considered capable of appreciating that work at a certain level. For instance, it seems quite odd to think that a person is capable of appreciating very difficult avant-garde art even though to do so would require a couple years of education.17 Although many in the art community find such devotion to understanding and appreciating art reasonable, I don’t think this is common among the population at large and so it makes little sense for the definition of ‘capable’ to include such extremes. But given the nature of aesthetic standards, in this view, it doesn’t really matter from a conceptual level how much we expect from the art appreciator because different definitions of ‘capable’ will simply lead to different distributions. If we use the extremely liberal version of capability then many works will be considered better than if we use a more conservative version; this would simply shift the curve that represents the amount of pleasure people are capable of deriving from it. Lastly, there is a related concern that can’t be so easily dealt with; when extensive training is required to prepare on observer for a work of art, the boundary between the value of the art and the value of the preparation seems blurred. Undoubtedly, good art requires some preparation for one to fully reap its benefits; however, for my purposes I will assume that the required preparation for works of art should be kept to the level so that most with some general cultural knowledge will be able to appreciate it with only limited specific preparation.18 This is the standard that we can use when figuring out the sort of aesthetic pleasure that an artwork is capable of producing in people and whenever I refer to the preference distributions later in this paper I will be using this standard.

As a theory about aesthetic prediction, Hume’s model (as interpreted by Mothersill and Levinson) makes several assumptions that have not previously been made explicit. Firstly, it requires that people have similar aesthetic capabilities, and that these capabilities are distributed in a (roughly) normal fashion. We can imagine a world where this isn’t the case; it is possible that there are different classes of art appreciators and that it is very difficult (if not impossible) for these different classes to enjoy the art designated as good by each other’s standards of taste. Wieand thinks that this is the world that we in fact inhabit, whereas I think this seems overly ridged. This is, at least, using the more liberal version of capability; it considers someone capable of enjoying a certain piece of art even though it would take a great deal of preparation for them to do so. However, if we don’t want to go with this more liberal version of capability, these groups may form based upon different levels of experience in art appreciation. In this sort of case there would be different standards of taste for each level of art experience; this simply acts as a means of guidance for people based upon the amount of preparation they have had because we can assume that not everyone will want to devote a great deal of their life in pursuit of art. There are, after all, many different sorts of activities in life through which we can pursue pleasure and fulfillment and so to assume that art must be preferred over other activities is unjustified.

In my view, the key requirement of a Humean type of standard is that there be a clear normally distributed structure of our capability to experience aesthetic pleasure. Even if we assume that the relevant experience with art is held constant between all observers there is still the possibility that people will experience different levels of enjoyment from different works of art because of the particularities of their psychologies. Hume himself mentions the likelihood that differences exist in the “humours of particular men” and “the particular manners and opinions of our age and country.”19 The common description of this diversity is that, given the existence of a standard, any divergence from that standard represents an error.20 However, this need not be the case if the standard itself takes such individual differences into account and does not treat them as error but instead as a natural fuzziness existent in any psychological phenomenon. The standard of taste, under this view, is the peak of the overall distribution of the capability to experience aesthetic pleasure. However, as the variance of this distribution increases, the predictive power of the standard decreases. This is because, when we make predictions using a standard, we make the assumption that we are near the peak of the distribution, but where we actually fall within the distribution is not known until we experience the art first hand. As the variance of the distribution increases (as the bell curve becomes shallower) the probability that we are near its peak also decreases. When this variance is exceptionally high, paying attention to the standard is no longer useful for predictive purposes. This is a fact about how well ordered our aesthetic inclinations are; the general feeling among those who lean toward a realist view of aesthetic standards is that these inclinations are very well ordered. I agree that the anecdotal evidence which most of us accumulate during our everyday aesthetic lives points to a great deal of structure in aesthetic response. Our common sense notions of aesthetics points to the sort of fuzzy structure that I am proposing; works that are appealing to a great many other people have a high likelihood of pleasing oneself as well. A similar thing can be said for horrible works.

There are, of course, many cases in which we see dramatic divergent feelings toward aesthetic objects, but this is typically coincident with some sort of acute cultural preparation for that art. For example, a good deal of prominent art within certain insular art movements requires that one become acquainted with it before it becomes enjoyable. Under a psychological view, this sort of variation is completely explainable; unlike the cognitively impenetrable visual system, it is highly likely that the cognitive areas responsible for our aesthetic responses are greatly influenced by other cognitive areas which are responsible for cultural beliefs and feelings. It isn’t all that surprising that aesthetic preferences would change with changes in our beliefs and preferences about other aspects of our life; although core aspects of aesthetic preference are probably fixed (or at least very resistant to change), it is unclear how many of our preferences that constitutes.21 The existence of works that stand the test of time is evidence for such a core aspect, but it is less clear how much this allows us to predict.

Objections and Clarifications

One likely concern about the adaption of Hume’s view as I have described it lies in a wish to keep a role for ideal critics; if the standard of taste is based upon a preference distribution then it seems like we should try to discover the distribution instead of asking ideal critics their opinions. The problem with this is that even though the ideal critics no longer determine the standard, there is good reason to believe that their opinions will track the standard. Additionally, finding out what the distribution is like would probably be insurmountably difficult; this is an empirical question, and one that doesn’t simply concern what people’s current preferences for art are (which might be found using a poll) but rather the sort of preferences that they are capable of having.

So, ideal critics are a useful tool for discovering the standard that the distribution would give us if we could discover it. But why think that the ideal critics track the true standard? Might the wish to use ideal critics simply be a holdover from Hume that doesn’t have relevance for the model I am proposing? There is a possibility that some other procedure would better track the true standard of taste set by the distributions, but I can’t think of one. Additionally, there are several good reasons why we might think that the ideal critics do track the standard. Their fluency with the great works that have widespread appeal regardless of cultural variation indicates that they probably have some sort of understanding of the properties that make those works so universally appealing, just as “folk” psychological concepts (such as how people act in certain situations) are still useful for prediction even though they are neither structured nor testable in the way of scientific psychological theories. This ability is also strengthened by the 5 attributes (which I quoted earlier) that Hume describes ideal critics as having; these likely facilitate the discovery of patterns in our aesthetic experience and the determination of how new objects fit into those patterns. Although their judgments are not perfect (they are not the standard itself), we can still use them to better determine which works deserve our time. It may be the case that ideal critics will have some preferences which require a great deal of initiation to share (we would, after all, expect ideal critics to spend a great deal of time studying and contemplating aesthetic objects); in those cases ideal critics, in their role as ideal critics, will have to reason counter-factually about what they would prefer if they were not so experienced. If they cannot do this then they would cease to be ideal critics because they couldn’t be relied upon to track the general distribution of preferences; they may still be good critics, but their views would only be fully relevant to whatever aesthetic subgroup to which they belong.

One could also raise a related concern with my usage of a rather conservative criteria for ones capability to enjoy an artwork. Those who have spent a great deal of time studying art may have some right to say that the art they appreciate most is actually better than the art appreciated by those who have devoted less time. The only way I think this sort of argument could get off of the ground is if the pleasure derived from less accessible art is substantially better than that of the rather easily accessible. However, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence of this. Although it is likely that the more experienced art appreciators will not gain nearly as much pleasure from the more accessible art, there is no reason to think that those appreciating inaccessible art are experiencing more (or more satisfying) pleasure overall than those who are appreciating more accessible art. We need to also remember that those who enjoy more accessible art likely spend their extra time (not being spent engaged with complicated art) on other pleasurable activities. It may be the case that those who have pursued art to the fullest would not feel as fulfilled if they did not pursue it; however, this hardly gives reason to those with different life goals to devote that amount of time to art when there are many activities from which one can derive pleasure.

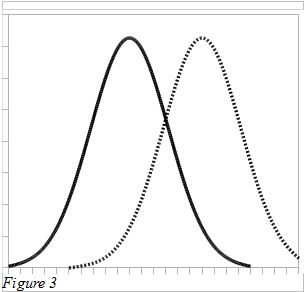

The final concern is the most serious; it threatens the notion that ideal critics can give us usable suggestions if the variance of art preferences is too large. Ideally, the suggestions of the ideal critics will lie at the peak of the distribution of preferences; however, this means that our actual preferences could lie to either side of the bell curve, with points further from the peak having a far lower probability than those closer. This gets more complicated when we are trying to decide between two different works both rated by an ideal critic. Even if we assume that the ideal critic is completely accurate in his/her judgments so that we are given the center locations of two curves, in most cases the curves will overlap in some location. These overlapping sections represent the probability that ones own preferences will be the opposite of the ideal critic.

In Figure 3, two preference distributions are graphed; they represent two different works of art. The peaks of the distributions are clearly different, so we would expect ideal critics to declare that the work represented by  the dotted line is clearly better than the one represented by the solid line. But for those who fall within the area where the curves overlap, actual aesthetic preferences may be the opposite of what the ideal critics predict. In the example above, this might be a devastating result for anyone wishing to predict preferences based upon the ideal critics. I think this is the worry that could sink the Humean picture of standards; however, its difficulty is contingent upon the variance of aesthetic preference distributions. If the typical variance of these distributions is rather small, then the probability of this sort of reversal is small enough such that ideal critics would still be useful for prediction. Unless the preference distributions of two works don’t overlap at all (which will be a rarity) there is always a chance of a reversal, but as long as the probability of this is only modest, then ideal critics are still useful. This is especially true given the lack of other reliable predictive methods.

the dotted line is clearly better than the one represented by the solid line. But for those who fall within the area where the curves overlap, actual aesthetic preferences may be the opposite of what the ideal critics predict. In the example above, this might be a devastating result for anyone wishing to predict preferences based upon the ideal critics. I think this is the worry that could sink the Humean picture of standards; however, its difficulty is contingent upon the variance of aesthetic preference distributions. If the typical variance of these distributions is rather small, then the probability of this sort of reversal is small enough such that ideal critics would still be useful for prediction. Unless the preference distributions of two works don’t overlap at all (which will be a rarity) there is always a chance of a reversal, but as long as the probability of this is only modest, then ideal critics are still useful. This is especially true given the lack of other reliable predictive methods.

Convergent Taste and Individual Style

One issue that has been raised by both Levinson22 and Alexander Nehamas23 is the seeming paradox between a standard of taste and personal style. If we think that there is only one true standard of taste, it seems as though we should all try to emulate that standard in our own judgments of aesthetic value. However, this threatens our desire for a unique sense of style that includes our aesthetic preferences. As Nehamas phrases this concern, “Even the idea that everyone might share one of my judgments sends shivers down my spine, although it is no less repulsive than the possibility that one other person might accept all of them.”24 There is an intuition that just as we wouldn’t desire the existence of a clone with our identical personality, we wouldn’t desire there to be an aesthetic clone; in fact, it seems as though our aesthetic judgments are a vital part of our personality. Both Levinson and Nehamas note that we don’t have a similar intuition about our moral views, as we would welcome agreement there. As a matter of fact, there are many facts of the world about which we seek agreement; those facts that fall under the category of style seem to be fundamentally different.

Levinson and Nehamas formulate very different solutions to this problem. Levinson faces the problem more directly, trying to resolve the tension between the existence of a singular standard of taste and our desire to have a unique aesthetic taste. He gives us several options to help resolve the tension; I think his third option is the most satisfactory, so I will address it in depth here.25 Levinson suggests that even if there is a clear hierarchy of aesthetic quality there are a good deal of works that would be judged as being approximately equivalent by the ideal critics. When this is the case, our individual aesthetic tastes can exhibit a personal style without conflicting with the standard of taste. Notice that this is exactly what we would expect if the standard of aesthetic judgments were characterized by distributions; when distributions overlap a great deal, then there is a good chance that our actual preferences may be the opposite of the standard ordering. This means that those works judged to be similar in quality are essentially considered equivalent because the probability that our actual preferences conflict with the ideal critic’s becomes far too high to rely upon them.

Nehamas recognizes the paradox as well but doesn’t offer any sort of clear solution. He spends a great deal of time developing the paradox into something that seems inescapable; according to him, “Taste, sensibility, character, style: they can’t exist without a background of principles, systems, and rules, but they are exactly what principles, systems, and rules have no room for.”26 For him, style is a vital part of the aesthetic world, not simply a problem for it; he claims that standards of taste draw people into groups but that a universal standard cannot bind together any single group. Still, this sort of position clarifies nothing for someone interested in experiencing art. There may be groups, but it is unclear which groups one should select before one has already become committed. The bulk of our aesthetic judgments might be based upon facts about our aesthetic style (psychological facts about the sort of aesthetic appreciator we are) but there are certainly some general facts about what works we can derive pleasure from. If we follow Nehamas’ reasoning then it would seem that we are adrift before we experience some initial artworks, the selection of which cannot be guided by any general standard of taste.

One benefit of the distribution view that I propose is that it avoids this paradox all together. It is true that there is a standard of taste and that there is quite a bit of agreement about the works from which we can derive the most pleasure, but this doesn’t mean that we always have to agree with the standard. Therefore, there is simply nothing puzzling about the issue of style. We are accustomed to paying attention to both the standard of taste as well as personal taste with relative ease and this reflects the real compatibility that exists between them. It is also quite apt that the comparison between aesthetic style and personality is so often made; I think this reflects a real similarity between them. Just as with taste, there are certain regularities in people’s personalities. Oftentimes, if a person’s personality exhibits certain attributes, then other attributes or tendencies can be predicted. This is, after all, what is behind the formation of personality types in psychology. So, personality attributes clump together in some standard ways but this does not mean that we can predict every attribute of a person’s personality simply by knowing their personality type; just as with taste, personality is an incredibly complicated construct with facets that are impossible to categorize easily. And also similar to taste, there are many sorts of different personalities one can have without being considered deficient.27

I want to bring up one final point that comes from Nehamas. He mentions the fact that, unlike with morality, taste has the effect of dividing people into different groups based upon shared taste.28 This is a good observation and also leads us to wonder whether there are better ways of predicting our aesthetic satisfaction than the ideal critics. Remember that ideal critics are generalists about aesthetic satisfaction; their clarity in aesthetic assessment and their knowledge of works that have stood the test of time allow them to make predictions about a broad range of people. This is because they are supposedly tapping into aesthetic tendencies that are very stable across cultures and times. However, as I discussed above, there are some aesthetic tendencies that are particular to certain cultures and sub-cultures; there is a good deal of variety in aesthetic taste and the ideal critics will tend to gloss over these differences. So, one could reason, it might be good for us to find out what sort of groups with which we share aesthetic tastes and then rely upon members of those groups for advice about what sorts of works to pursue.29 And indeed, this seems to be the sort of strategy people often use to discover new art that might bring them aesthetic pleasure.

This sort of segmentation of people according to past aesthetic preferences at least has some prima facia legitimacy. There is also an explanation of why this might work from the distribution theory that I have been using. We don’t know where in any distribution our preferences will lie, but if we can find someone with similar preferences as our own then there is a good chance (if the structure of different preferences is well ordered) that our own preferences will be closer to that person’s than to the ideal critic’s. This would work because it could tell us how a cognitive system responsible for aesthetic preferences similar to our own responds to a given aesthetic object; ideal critics can only tell us how people in general will respond because their standard tracks the tendencies that are universal. If this is a better way of predicting our aesthetic preferences, then it might sink Hume’s entire method of using ideal critics to track a single standard of taste that works for most people. But I think there is a major flaw in this sort of method that might offer some support to the reign of ideal critics. Although those in our own aesthetic group may be able to inform us of lessor works (as defined by the ideal critics) that might cause us a great deal of aesthetic pleasure (yet would not be recommended by an ideal critic), they would likely miss the greatness of works that might be universally appealing. This is because non-ideal critics typically possess prejudices and nuances of taste that we do not share with them. Even though people in an aesthetic group might share many aesthetic tendencies with each other, they will also differ in many ways. This will cause non-ideal ciritcs to have far more chaotic aesthetic judgments than ideal critics who are able to judge aesthetic worth through rather pure reasoning.

For instance, we might have a great love for a single band and consult with a group of other like-minded individuals about the quality of other music. An ideal critic might pick out a few works from that band that are universally appealing but largely consider other works to be substandard. In this case, the standard from the ideal critic does not match the enjoyment that people in the “fan club” are obtaining from the particular band’s music. In instances when other music is very similar to this band, it might make more sense for members of the fan club to seek advice from other members instead of the ideal critic. But the usefulness of this method will likely not extend to works that are significantly different from that of the original band; individual differences in tastes of the fan club members will likely differ in substantial and complicated ways that will probably cause a person who relies upon advice from them to avoid works they would probably enjoy; they will instead spend time with works that yield comparatively only moderate amounts of satisfaction. If the members of the fan club are totally isolated then they would never listen to Bach or the Beatles even though these works would probably bring them great satisfaction (as they do for almost everyone).

Conclusion

Although the picture I offer based upon the distribution of aesthetic preference seems very different than most current views of Hume’s standard of taste, I see it as simply an explication of models that claim the existence of a defeasible standard of taste. The standard of taste provided by ideal critics is true enough for most individuals but is defeasible owing to the variance in psychological processes that affect aesthetic judgments. The main difference between my view and others is that it is explicit about why aesthetic standards are defeasible; they are defeasible because aesthetic preference varies between people in the form of a roughly normal distribution. Although it is difficult to know details of the distribution’s structure, a normal distribution would match the experiential evidence we have that there are clear standards of taste. This conception of the standard of taste also clarifies and shows the limitations of the predictive power of Humean ideal critics. By taking the psychological nature of aesthetic experience seriously we can understand aspects of aesthetic experience, such as the desire for personal style, without succumbing to paradox.

Citations

Carroll, Noël. “Humes Standard of Taste.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 43 (1984): 181-194.

Child, Irvin L. “Personality Correlates of Esthetic Judgement in College Students.” Journal of Personality 33 (1965): 476-511.

Furham, Adrian, and Margaret Avison. “Personality and Preference for Surreal Paintings.” Personality and Individual Differences 23, no. 6 (1997): 923-935.

Goldstein, E. Bruce. Sensation and Perception. 6th ed. Wadsworth, 2001.

Hume, David. Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary. Eugene F. Miller ed., 1987(1742). accessed at: Library of Economics and Liberty, <http://econlib.org/library/LFBooks/Hume/hmMPL.html>.

Jameson, Kimberly A., Susan M. Highnote, and Linda M. Wasserman. “Richer Color Experience in Observers with Multiple Photopigment Opsin Genes.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 8, no. 2 (2001): 244-261.

Levinson, Jerrold. “Hume’s Standard of Taste: The Real Problem.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 60 (2002): 227-238.

—– “The Real Problem Sustained: Reply to Wieand.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 61 (2003): 398-399.

—– “Artistic Worth and Personal Taste.” Unpublished.

Mothersill, Mary. “Human and the Paradox of Taste.” in Aesthetics: A Critical Anthology. 2nd ed., edited by George Dickie, Richard Sclafani, and Ronald Roblin, 269-286. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1989.

Nehamas, Alexander. Only a Promise of Happiness: The Place of Beauty in a World of Art. Princeton University Press, 2007.

Wieand, Jeffrey S. “Hume’s Real Problem.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 61(2003): 395-398.

Notes

1part 1, essay 23 in Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary.

2The existence of the sex-linked genetic mutation that leads to tetrachromatic color vision (only occurring in women) has been known for quite some time, though there has been a good deal of debate about the percentage of the population that is affected. There is especially a great deal of debate about the relative contributions of the tetrachromatic mutation and other cognitive differences between men and women that could contribute to differences in aesthetic perception between the sexes. For a recent introduction to the subject, see Jameson, Highnote and Wasserman, “Richer Color Experience in Observers with Multiple Photopigment Opsin Genes.”

3There could be some small benefits of having very precise color discrimination but I don’t think these could ever out-weigh the trouble caused by tetrachromatic vision. The sorts of tasks that humans must be able to do in order to be successful simply do not require such a level of color discrimination. These problems would primarily occur when tetrachromatics observe artifacts because, I suspect, that color among natural objects is patterned in a way to avoid this sense of clashing colors. However, the world of artifacts is still an important world that we must deal with..

4Most of what I say about the visual system in this section is considered general knowledge in the vision science community; explanations can be found in an introductory text such as Goldstein, Sensation and Perception.

5These numbers would have no meaning if they we did not know the scale of luminance. For reference, the brightest most CRT monitors can display a white light is about 250 cd/m2. With this in mind, the amount of luminance difference for which we find total agreement exhibits far less variance than any judgments based upon more cognitive processes.

6This is normally found by presenting a person with a test stimulus and various comparison stimuli in succession (asking the person whether the test stimulus is brighter or dimmer than the comparison stimulus) and then inferring the perceived luminance of the test stimulus from the entire set of judgments. This method is called the method of constant stimuli.

7The distinction between cognitively penetrable and impenetrable areas of the visual system is most easily understood by considering experience with some visual illusions. For instance, the Müller-lyer Illusion (where two lines of equal length are shown together except one has “arrow” ends and the other has “tail” ends, causing the one with tail ends to appear longer) is almost completely cognitively impenetrable; no matter how sure we are that the the two lines are of the same length, we can not see them as so. However, a Necker cube can be “flipped” by devoting certain higher level cognitive resources to our perception; so, in this case, top-down activity in the brain is affecting what we perceive. I should also mention that I use the term ‘cognitive’ to refer to any higher-level brain activity, including (but not limited to) emotional, computational, linguistic, and memory areas.

8Examples of these relatively high variance distributions abound in complex human behavior. One example that might be helpful is a test in some sort of academic setting that relies upon an objective measure of performance. The results of these sorts of tests often form just such a normal distribution; the performance of students varies for many reasons (preparation, past knowledge of the material, cognitive ability, test anxiety) to produce that distribution of results. If this sort of cognitive task were like a perceptual task then we would expect almost everyone to score within a few percentage points of each other, and this almost never occurs.

9There are reasons why polls are the wrong way to learn about aesthetic preferences but I will deal with that a little later.

10There might be a easy reply to this assertion; just as in the aesthetic case, we do in fact ignore the perceptual abilities of some because they diverge too greatly from the norm. However, the claim I am making is that the number of people with non-standard perceptual abilities is small enough such that the standard we should use is obvious. We should also remember that many people with non-normal perceptual abilities have substantial deficiencies in their ability to operate in the world unaided by corrective devices (such as glasses). Those remaining people who are not negatively affected by their perceptual uniqueness are few enough to not cause a problem for the perceptual standard. This is not the case for aesthetic standards.

11This is known as the Weber-Fechner law.

12This comes mostly from Mary Mothersill’s “Hume and the paradox of taste”.

13Hume, “Of the Standard of Taste”, part 1, essay 23 in Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary, paragraph 24

14Jerrold Levinson “Hume’s Standard of Taste: The Real Problem”

15Jeffrey Wieand, “Hume’s Real Problem.”

16I’m more concerned that we take some measure of cognitive ability seriously than IQ in particular; though the issue of what exactly IQ tests measure is somewhat controversial, I find it uncontroversial that there is some characterization of general cognitive ability that we feel is important.

17I suspect that most art can be appreciated fully (or at least enough) with far less of a commitment, but there may be cases where the dedication needed to fully appreciate the artwork is substantial.

18To be more explicit, I’m thinking that the sort of education in the liberal arts one receives at a university (and this isn’t a whole lot) should be enough for one to understand and enjoy art with limited artwork-specific preparation. I make no claims that this is the best position to take but only that it seems to reflect the situation in which most art-interested people find themselves.

19Hume, “Of the Standard of Taste”, part 1, essay 23 in Essays, Moral, Political, and Literary, paragraph 29

20I think this divergence between the amount of aesthetic pleasure we experience from a work of art and the amount we think we should experience (or the quality we judge the work to have) is behind Carroll’s worries in “Hume’s Standard of Taste” that there is no necessary connection between the value of a piece of art and the amount of aesthetic pleasure we derive from it. Given the structure that I’ve described, it is expected that our own art preferences may vary slightly from the standard, so we may sometimes have to recognize that those preferences will differ from what we know the standard of value is (i.e. the pleasure we would expect others to derive from the work) but this should be minimal. However, if we take Carroll’s view seriously then it threatens to make the standard of taste irrelevant because it could no longer predict the sorts of works that we will find pleasurable. He gives the example of Stephen King who he takes to be a bad writer but whose work still brings him a great deal of aesthetic pleasure. I don’t see how this distinction is at all helpful. It is true that Stephen King does not produce works of the same depth as William Golding (to use his example) but this seems to presuppose that complexity and depth matter for the standard regardless of the aesthetic pleasure they are able to bring us; if this were true then such a standard would run into the problem of being irrelevant for us. I suspect that examples such as Stephen King are actually aesthetically valuable but not in a complex way; however, it is often the case that we do not desire these sorts of complex experiences and then these simpler pleasures do quite well.

21This is an empirical matter and I don’t make any claims about the answer. However, there is some evidence that aesthetic judgment is affected by personality, though the construct for judgment used in many of these studies is more related to the polling procedure than aesthetic capability. For examples, see Furnham and Avison, “Personality and Preference for Surreal Paintings,” and Child, “Personality Correlates of Esthetic Judgment in College Students.”

22Jerrold Levinson, “Artistic Worth and Personal Taste.”

23Alexander Nehamas, Only a Promise of Happiness; most of this discussion is from pp 78-91

24Ibid., p. 84

25I choose this solution mainly because I believe it is the only one that fully deals with the problem. Levinson’s first response portrays taste as unavoidable error to obtain the preferences dictated by the standard; he recognizes that this isn’t very satisfying and I agree. The second solution redefines the problem so that unique and authentic processes of coming to the correct aesthetic judgments are enough to give us aesthetic individuality. Although this does help in some way, it doesn’t resolve the intuition that wide-scale agreement on aesthetic value, regardless of how we come to it, takes away from our capability to have a style. His fourth solution claims that a difference in ones internal experience of art without an accompanying difference in outward judgment is enough to constitute unique style; this just seems wrong given the fact that outward aesthetic choices are usually considered to be a hallmark of personal style as it is commonly conceived.

26Only a Promise of Happiness, p 85.

27Of course, some personalities are considered deficient but that is only the case because they interfere with other aspects of life that we find valuable. We could make a similar case against the tastes of some individuals if those tastes bring about more pain than pleasure for them.

28Only a Promise of Happiness, p 86.

29This seems to be a useful extension of Wieand’s thought that the standard of taste tells us what sort of people we are.

This essay was written by me for a graduate course at the University of Maryland.